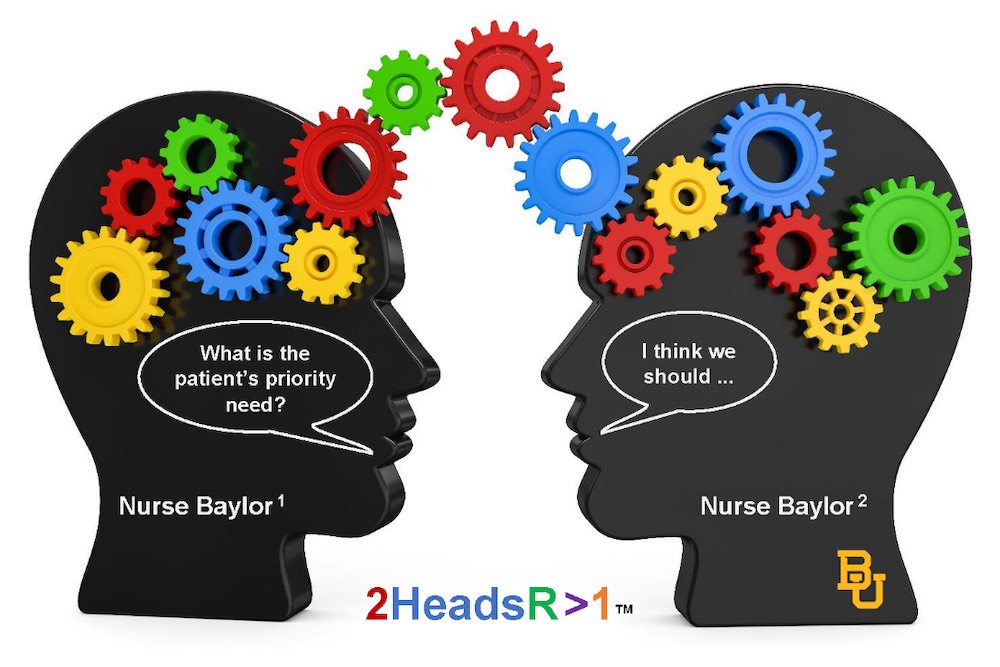

Two heads are better than one, or so the saying goes. The clinical simulation team at Baylor University Louise Herrington School of Nursing created an innovative strategy for role assignment in healthcare simulation built on this adage and learners are not the only ones reaping the benefits. Faculty are gaining new insight into their learners’ critical thinking skills and peers who are serving as observers during the medical simulation scenario are more engaged. Ultimately, the Two-Heads-Are-Better-Than-One (2HeadsR>1) strategy encourages collaboration and prioritization, while highlighting critical thinking and clinical reasoning. This HealthySimulation.com article explains what this strategy entails, and how to implement this type of thinking across healthcare simulation education settings.

Role-playing via role assignment is a necessary component of simulation, as roles are the vehicles that drive the healthcare simulation scenario to meet desired goals (INACSL Standards Committee, Facilitation, 2021). However, a lack of data identifying best practices for role creation and assignment may leave clinical simulation educators wondering what the most effective approach is. The Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice (HSSOBP) speaks of identifying roles and orienting participants to their roles, but little guidance is provided regarding the types of roles to include (INACSL Standards Committee, PreBriefing, 2021).

In nursing education, a common practice when assigning roles for a clinical simulation scenario is to portion out a nurse’s duties among several learners; these tasks might include documentation, medication administration, procedures, and assessment. This portioning of duties among multiple participants allows learners to divide and conquer, rather than prioritize and delegate.

Learners often challenge this distribution of nursing tasks among multiple parties, saying this is not a realistic representation of a nurse’s workload. Designating primary and secondary nurse roles is another common approach in nursing simulation, but this often causes the learner assigned as the secondary nurse to abdicate responsibility during the simulation to the one selected to be the primary nurse (Carey et al., 2018).

Thus, the 2HeadsR >1 strategy for role assignment in simulation assigns two learners to act in the role of one nurse. The learners are instructed to move and act as if they are one person; they cannot be in two places at one time, nor can they simultaneously engage in two separate activities. The strategy also encourages learners to collaborate, prioritize patient care, and delegate as needed.

The two learners verbalize their clinical reasoning with one another, facilitating the development of a plan of care for the simulated patient. If there is a difference of opinion regarding the appropriate action to take, the learners must provide the rationale for their plan in an attempt to sway their partner.

Read More: “2HeadsR > 1 : A Strategy for Role Assignment in Nursing Simulation From Baylor University”

Overall, an agreement is necessary in order to proceed in their care of the simulated patient. If at any time the two learners in the role of the nurse forget the 2HeadsR >1 premise and split apart tending to different patient needs, the healthcare simulation facilitator must provide a gentle reminder over the intercom that they need to act as one (Carey et al., 2018).

The conversation between the two learners during the scenario is an example of the “Think Aloud” (TA) technique. This strategy is utilized across cognitive research but is relatively new to healthcare simulation. TA is much more than a narration of the actions being performed; the technique is the articulation of the thinking behind the actions (Carey et al., 2018).

When not in the active participant role, learners observe the action via live video streaming, from the debriefing room across the hall. The 2HeadsR >1 strategy for role assignment allows those watching the clinical simulation scenario to follow the thinking behind the actions and heightens the level of engagement of learners in the observer role.

The 2HeadsR >1 strategy also affords clinical faculty members a peek inside the heads of their learners, facilitating the understanding of their thought processes behind the observed actions. Assessment of critical thinking and clinical decision-making skills is possible from a new perspective (Carey, et al., 2018).

Further, when two learners function as one nurse, the more dominant member may unduly influence the course of action, perhaps taking the pair in the wrong direction. If the other learner fails to recognize the error in judgment or does not speak up when a misstep is identified, the clinical simulation scenario will proceed accordingly.

The simulation facilitator and clinical faculty member monitor the dialogue between the two learners and if one learner’s thinking is leading the pair in the wrong direction, the educators have several options:

- Allow the situation to unfold and let the learners experience the consequences of their actions

- Stop the scenario and explore the learners’ thinking during a debriefing session

- Have a simulation educator enter the scenario

- Effect change by offering cues or by seeking clarification (Carey, et al., 2018).

Reflective education during the debriefing will investigate alternate choices and provide time for both learners to share their thoughts and feelings regarding the clinical simulation (Mariani, Cantrell, Meakim, Prieto, & Dreifuerst, 2013).

Theoretical Basis for the 2HeadsR>1 Strategy

The 2HeadsR >1 strategy is built upon the evidence in support of collaborative cognition. Research in this area shows that when two people combine their sensory information, the resulting performance is oftentimes better than either individual could execute alone; this is especially true if the individuals engage in open dialogue and express opinions with each other.

Collective decision-making can surpass that of either individual and collaborative cognition is enhanced by some degree of diversity among the thinking styles or personalities of the members (Bahrami, et al., 2010). When utilizing the 2HeadsR >1 strategy, healthcare simulation facilitators should be aware that learners who feel comfortable working with each other may, during the clinical simulation, perform at a higher level than would a pair less familiar with one another (Carey et al., 2018).

Impact on Learning of the 2HeadsR>1 Strategy

The 2HeadsR >1 strategy affords clinical faculty members a new perspective for assessing critical thinking skills. Clinical instructors, observing from the control room, follow the healthcare simulation scenario and gain insight into a learner’s decision-making. Viewed actions can be linked to verbalized thought processes, revealing levels of clinical reasoning and potential gaps in learning.

Additionally, the 2HeadsR >1 strategy allows clinical faculty to identify learners needing more one-on-one time during clinical hours. Instructors gain valuable insight into their learners’ clinical reasoning when the 2HeadsR > 1 strategy is employed and can take the necessary steps to ensure learners are providing safe and effective patient care in the clinical setting (Carey et al., 2018).

Assigning two learners to operate as one nurse decreases role confusion and empowers both participants to take any nursing action they deem appropriate. Acting alongside a “buddy” decreases anxiety which improves learning; learners appreciate having a peer by their side to discuss options and explore questions.

Prior to the implementation of the 2HeadsR >1 strategy, role confusion often resulted in students standing idle during the clinical simulation scenario. Some participants expressed frustration when they knew the appropriate actions to take but were not assigned the role responsible for those interventions (Carey et al., 2018).

Opportunities to practice teamwork, collaboration, and professionalism abound throughout the healthcare simulation activity and mimic the role of nurses working as members of interdisciplinary teams in the clinical setting. TA, fostered by the 2HeadsR >1 strategy, raises learners’ awareness of the knowledge and abilities they possess, dispelling feelings of inadequacy that they often internalize. Learners report increased confidence after participating in simulation utilizing the 2HeadsR >1 strategy; they reflect on their ability to recognize critical elements, make sound judgment calls, and initiate appropriate interventions in a timely manner (Carey et al., 2018).

The 2HeadsR >1 approach allows additional learners to be involved as observers and gain insight from the thinking aloud of their classmates. Learners find following the thinking behind the observed actions and evaluating skills such as communication, prioritization, delegation, and situational awareness easier. Learner observers are better prepared to participate in the debriefing session (Carey et al., 2018).

Teachable moments are sometimes missed in the healthcare simulation and clinical practice settings when a learner performs the right action for the wrong reason. In other words, the instructor may see a learner take the appropriate action in a given situation and assume the learner understands why he or she performed that act.

However, the learner may be operating under an assumption based on a previous experience (Dreifuerst, 2015). Understanding how often this occurs may be difficult, but in every instance, this forfeits a learning opportunity for the learners and may also reinforce faulty cognition.

TA, initiated by the 2HeadsR >1 strategy for role assignment, exposes inaccurate thinking even when the learner provides the proper care. Clinical faculty and sim facilitators recognize mistaken or misguided thinking and can capitalize on this teachable moment.

The 2HeadsR >1 strategy fosters the development of the second QSEN (Quality and Safety Education for Nurses) competency: Teamwork and Collaboration. The two learners working as one nurse, recognize their own strengths and limitations; they learn the benefits of teamwork and appreciate the positive effect on patient care.

The 2HeadsR >1 strategy encourages learners to practice different styles of communication while conversing with the patient, a member of the healthcare team, and one another. Differences of opinion must be explored and ultimately resolved to proceed with patient care. Repeated exposure to the QSEN competency of Teamwork and Collaboration during simulation scenarios employing the 2HeadsR > 1 strategy will prepare the learners to provide higher quality and safer nursing care upon graduation (Carey et al., 2018).

Call to Action – More Research Needed on Role Assignment in Healthcare Simulation

The HSSOBP provides detailed guidelines for developing, implementing, and evaluating clinical simulation-based learning activities, but as previously mentioned, instruction on assigning roles to participants is lacking (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021). Strong evidence exists supporting the use of the observer role during healthcare simulation activities but guidance on the use of this strategy during simulation-based learning is not provided in the new standards.

In conclusion, more research is certainly needed on the effect of role assignment strategies used in healthcare simulation. Often, logistics such as time, space, and the number of participants drive the decisions regarding role assignment, without sufficient consideration for the impact on learning.

[toggles behavior=”toggle”]

[toggle title=”References:”]

- Bahrami, B., Olsen, K., Latham, P.E., Roepstorff, A., Rees, G., & Frith, C.D. (2010). Optimally interacting minds. Science, 329, 1081-1085.

- Carey, J., Woo, J., Lindley, M., Lewis, A.Z., & Wilburn, B. (2018). A strategy for role assignment in simulation using collaborative cognition. Journal of Nursing Education, 57(11), 694-697. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20181022-13

- Dreifuerst, K.T. (2015). Getting started with debriefing for meaningful learning. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11(5), 268-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2015.01.005

- INACSL Standards Committee, Persico, L., Belle, A., DiGregorio, H., Wilson-Keates, B., & Shelton, C. (2021, September). Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best PracticeTM Facilitation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 22-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.010.

- INACSL Standards Committee, McDermott, D.S., Ludlow, J., Horsley, E. & Meakim, C. (2021, September). Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best PracticeTM Prebriefing: Preparation and Briefing. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 9-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.008.

- Watts, P. I., Rossler, K., Bowler, F., Miller, C., Charnetski, M., Decker, S., Molloy, M. A., Persico, L., McMahon, E., McDermott, D., & Hallmark, B. (2021). Onward and upward: Introducing the healthcare simulation standards of Best PRACTICETM. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.006

[/toggle]

[/toggles]