When learners move into clinical experiences they often remain focused on skills and may have difficulty applying the theoretical knowledge they learned in the classroom. Simulation provide a wonderful method for learners to interrelate all aspects of care, develop reflective thinking and become better clinicians. Simulation has been well established as an effective pedagogy. Recently a new form of simulation the Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice (RCDP) is emerging in medical education. In RCDP, learners rapidly cycle between deliberate practice and directed feedback within the simulation scenario until mastery is achieved.

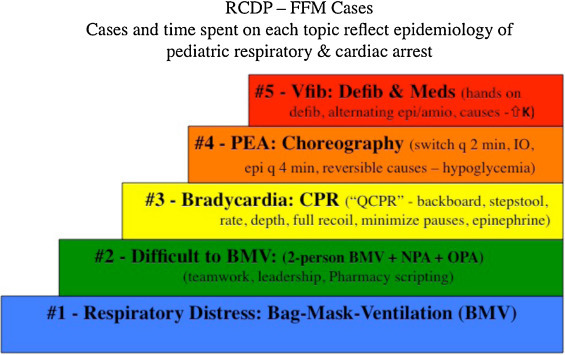

Dr. Betsy Hunt from John Hopkins University was concerned that residents who had completed a PALS course and a 2 hour “Just in Time” Refresher workshop, were still slow to initiate defibrillation and other components of PALS. Dr. Hunt noted that for critical life saving activities where time is of the essence, traditional simulation might not ensure competency. Since some of these activities were life saving interventions, residents could not be allowed to fail. D.r Hunt introduced a two hour RCDP PALS course for pediatric residents. Whereas traditional simulation involves debriefing and reflection, RCDP flips this process and includes directed feedback and deliberate practice. At first this might appear to switch the emphasis from the learner to the teacher, but there are some occasions such as in a code, where the learners just need to know the answer. Dr. Hunt sites the example of a NASCAR pit crew where all crew members must complete their part in an exact sequence.

Important components of RCDP include:

- Repetition, muscle memory

- e.g. Chest compressions in CPR

- Pattern recognition

- E.g. Practices with ACLS/PALS cards

- Use action linked statements – e.g. if there is no pulse, I start chest compressions.

- Scripts – can be used for different team members

- Choreography – where people stand and place equipment – particularly key when multiple people in the team.

- Memory Prompts, cognitive aids.

The simulation participants may expect the simulation to be conducted using the established process. The learners need to be informed ahead of time that RCDP is a different process. Participants should feel confident that confidentiality will be maintained. The participants should know they will be interrupted and will need to repeat procedures until they become competent. They will also receive information about how to improve. Many learners will welcome the opportunity to repeat until they have mastery. This methodology applies equally well to individuals and to team interventions. Practice is key.

Dr. Hunt mentions that adrenalin can either help or hinder people’s actions in stressful situations. “Amygdala hijack” is where the emotional center overcomes the rational center of your brain and this can affect performance. Participants practice until they actually “over-learn”. During an actual code, the over-learning can compensate for the amygdala hijack.

The first simulation is not interrupted and is used to identify knowledge gaps. Adult learners need to accept that they do not know something before they will put effort into learning. Following the simulation, a debriefing is conducted to identify gaps and provide information about the correct way to complete interventions. From the second scenario onwards, when errors are made, the scenario will be stopped, rewound 30 seconds and then repeated.This is unlike traditional simulation where traditionally the facilitator never interrupts. The scenario will be repeated until the facilitator is confident that the participants have mastery of the subject.

To date, RCDP has been used for training related to critical components such as the interventions found in ACLS or PALS. However, RCDP could be used in a basic nursing courses for example when practicing safe medication administration. Perhaps in the first scenario a student fails to check patient ID. This gap would be discussed during the first debrief. The scenario will then be repeated, stopped, rewound, until mastery is achieved. Tell the students their error and offer tools to help learners complete the medication administration safety and in a timely manner. Practice until the student get the intervention right. If a student continues to perform incorrectly, help the student to understand their incorrect frame of reference.

Gradually increase the complexity of the scenario. Add additional complications for ACLS or PALS or for the example with beginning nursing students add medications that require vital sign or lab interpretation before administration. As the scenario becomes more complex, do not let learners make mistakes for activities that they had performed correctly in the first simulation. Finally Dr. Hunt points out that facilitator enthusiasm and support for learners makes all the difference.

Today’s article was guest authored by Kim Baily PhD, MSN, RN, CNE, Simulation Coordinator for Los Angeles Harbor College. Over the past 15 years Kim has developed and implemented several college simulation programs and currently chairs the Southern California Simulation Collaborative.

Have a story to share with the global healthcare simulation community? Submit your simulation news and resources here!