In response to the closing of healthcare educational programs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some healthcare simulation programs have changed their experiential learning experiences from face to face activities to Virtual Reality. Today Dr. Kim Baily PhD, MSN, RN, CNE, previous Simulation Coordinator for Los Angeles Harbor College and Director of Nursing for El Camino College, explores some of the literature, advantages and disadvantages of this ground breaking VR technology in clinical education during the Coronavirus pandemic.

The Value of Virtual Reality in Healthcare Simulation

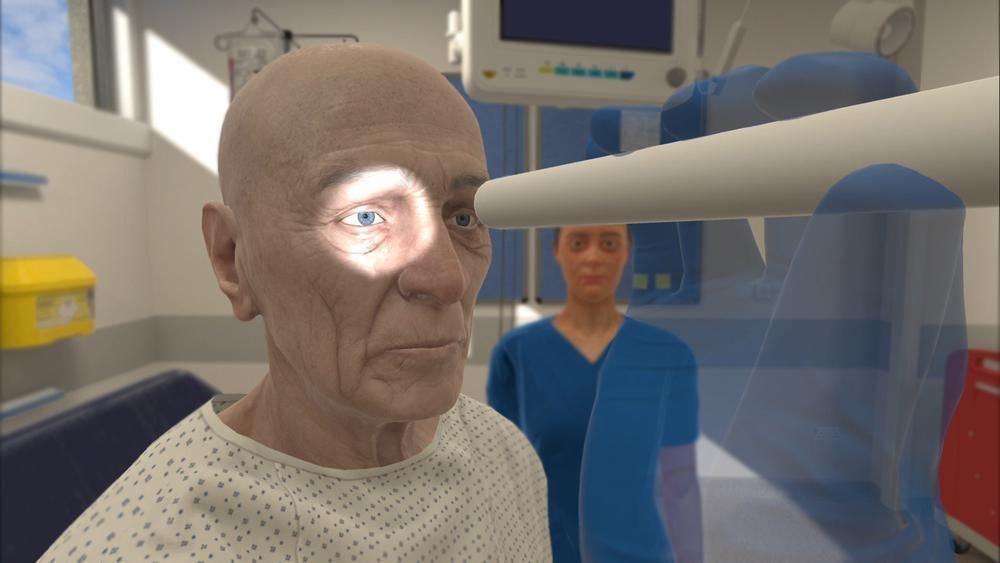

VR is defined as the computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional image or environment that can be interacted with in a seemingly real or physical way by a person using special electronic equipment, such as a helmet with a screen inside or gloves fitted with sensors. VR allows healthcare students and licensed practitioners to experience real-life experiences without real-life consequences. If healthcare schools adopt this type of educational strategy, accrediting bodies and state boards will want to know how effective VR is and what are the benefits and drawbacks of this type of pedagogy. This article summarizes a recent article about VR by Jack Pottle, co-founder and chief medical officer, Oxford Medical Simulation, London, UK (Pottle, J. VR and the Transformation of Medical Education, Future Healthcare Journal 2019 Vol 6, No 3: 181–5), as well as explores some of the latest research covering VR in medicine.

Pottle notes that VR offers the learner the opportunity to become completely immersed in a given clinical situation using equipment that can be set up virtually anywhere. This experience is different to screen based learning, since the learner becomes surrounded by the experience. Pottle writes “By contrast, interactive VR involves a totally immersive, dynamic, adaptive, interactive world”. The experience involves possible interaction with all members of the health care team and in different clinical settings. Virtual patients have different personalities and characteristics, as well present with an endless variety of physical, emotional and psychological states. Following the experience, the learner is virtually debriefed and receives detailed feedback on their behavior during the scenario.

Advantages:

- Relatively low cost, simple equipment which is easily portable and takes up little space. Easy set up, easy for faculty to learn.

- Faculty need not be present.

- Available as an adjunct to clinical practice.

- Available for repeated deliberate practice where learners can repeat the experience as many times as they want or need.

- Allows learners to make mistakes without any risk of harm to patients.

- No specific location required, can be set up in a clinical area.

- Convenient, learners can use during down time or breaks.

- Fun and psychologically safe learning environment.

- Relatively easy to imbed standardized policies and latest evidence-based practice.

- Relatively easy to standardize learning experiences.

- Relatively easy to monitor learner performance and generate data. Additional experiences may be offered to learners who have difficulty with experiences.

Disadvantages:

- Not effective for teaching hands on assessment skills such as palpation.

- Facilitates some components of skills training although may be limited for some skills.

- Limited ability to assist in developing communication skills.

- Limited use for in situ simulation.

- Limited use in practicing patient communication. However, just practicing explanations and offering support provides the learner an opportunity to verbalize responses and evaluate their own performance.

- Senior educators may consider VR a game and not take the experience seriously.

Pottle notes that VR is one educational option that would not replace in person simulation or clinical experiences but it does offer another educational tool. Aviation and the military have long found VR to be effective. “In fact, the aviation industry credits VR-based simulation as a major contributor to a nearly 50% reduction in human error-related airline crashes since the 1970s”. In the medical simulation field, medical students have been found to gain more knowledge with VR than screen-based. VR has been used extensively in surgical training programs and is increasingly being used in healthcare education and to provide objective clinical evaluations.

A 2016 literature review by Samadbeil et al., provided a number of instances where VR has been successfully used in medical education . (Samadbeil et al., The Applications of Virtual Reality Technology in Medical Groups Teaching. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2018 Jul; 6(3): 123–129). The study noted that a higher accuracy in medical practice by people trained through VR has been reported in 20 (87%) studies. “The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has announced that it is better for residents to be trained by simulation tools before attempting any interventions on patients because it has been effective in performing invasive hemodynamic monitoring, mechanical ventilation, and standardized educational intervention”. Although the study pointed out some negative effects of VR, there were many more positive effects:

- Increase in accuracy and accuracy of trainers and reduction of errors

- Improving the teamwork in the medical team.

- Decrease of harm to those being treated by people who are trained by VR, decrease in mistakes and more successful surgeries

- Increase in skills of learners.

- Better learning of anatomical positions.

- Better understanding of the exterior and interior space relationships between the organs.

- Valuable approach for Standard and unified education of medical groups.

- Increase in the skill of surgeons.

- Increase in the safety of the physician and patients.

- Decrease in the costs and increase in the efficiency.

- Overall performance improvement.

The overall reduction in cost, usability and the possibility of using VR for learner evaluation makes it likely that its use will expand in the future. In the current COVID pandemic, VR offers an alternative to traditional simulation and clinical time. Emphasis is placed on learner independence and decision making. VR also facilitates distance learning where learners are spread out in different geographical locations.

A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda (Radianti et al.), used systematic mapping to identify design elements of existing research dedicated to the application of VR in higher education. The reviewed articles were acquired by extracting key information from documents indexed in four scientific digital libraries, which were filtered systematically using exclusion, inclusion, semi-automatic, and manual methods. The review emphasizes three key points: the current domain structure in terms of the learning contents, the VR design elements, and the learning theories, as a foundation for successful VR-based learning.

In Virtual Reality Simulation in Nontechnical Skills Training for Healthcare Professionals (Bracq et al.), found that “the general conclusion of these studies is that VR simulators offer promising opportunities for NTS training of health professionals. Their acceptability as an NTS training tool is validated either directly or through one or more of its predictors as defined by Nielsen’s model of system acceptability: validity or fidelity, usefulness or utility, efficiency, effectiveness or efficacy, and usability. The acceptability of VR simulators is not assessed alone but together with teamwork, situation awareness, stress management, self efficacy, and leadership, or with several NTS using a dedicated assessment tool such as NOTECHS or NOTSS.

In Predicting Nurses’ Use of Healthcare Technology Using the Technology Acceptance Model, Strudwick explains that “the benefits of healthcare technologies can only be attained if nurses accept and intend to fully use them. One of the most common models utilized to understand user acceptance of technology is the Technology Acceptance Model.” The review shared here explains that previously the model and modified versions of it have only recently been applied in the healthcare literature among nurse participants. A modified Technology Acceptance Model with added variables could provide a better explanation of nurses’ acceptance of healthcare technology. These added variables to modified versions of the Technology Acceptance Model are discussed, and the studies’ methodologies are critiqued. Limitations of the studies included in the integrative review are also examined.

Check Out These VR Companies Revolutionizing Healthcare Education (and their COVID-19 Support Offers):

- UbiSim: Simulation Virtual Recorder

- OMS: Open Access for US, UK and CAN Providers

- VRPatients: New EMS VR Training Solution

- Health Scholars: $1M in Grant Funding for ACLS Trainers

- Fundamental VR

- Precision OS

- OSSO VR

Additional Reading:

Virtual reality and the transformation of medical education (Pottle): Medical education is changing. Simulation is increasingly becoming a cornerstone of clinical training and, though effective, is resource intensive. With increasing pressures on budgets and standardisation, virtual reality (VR) is emerging as a new method of delivering simulation. VR offers benefits for learners and educators, delivering cost-effective, repeatable, standardised clinical training on demand. A large body of evidence supports VR simulation in all industries, including healthcare. Though VR is not a panacea, it is a powerful educational tool for defined learning objectives and implementation is growing worldwide. The future of VR lies in its ongoing integration into curricula and with technological developments that allow shared simulated clinical experiences. This will facilitate quality interprofessional education at scale, independent of geography, and transform how we deliver education to the clinicians of the future.

MD+DI: Osso VR Expands Its Reach, Shares Study Results: A just-released study entitled “Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Virtual Reality Tool to Teach Surgical Technique for Tibial Shaft Fracture Intramedullary Nailing” conducted by UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine shows that the surgical performance of Osso VR users “improved by 130% and their speed was 20% faster,” Justin Barad, MD, CEO and co-founder of Osso VR, told MD+DI. “These are not subtle differences. Research is showing that VR users are faster and more competent.” He added that just after 30 minutes of VR training, the “effect is startling.”

Subscribe for the Latest VR in Healthcare Resources!

Have a story to share with the global healthcare simulation community? Submit your simulation news and resources here!